Also, readers of this blog seem to respond to the "disclosure" posts more than any others--those and the post-season "Saratoga Highlights" posts. And, yes, like the "Saratoga Highlights," I have fun doing the "Disclosures." Self-therapy?

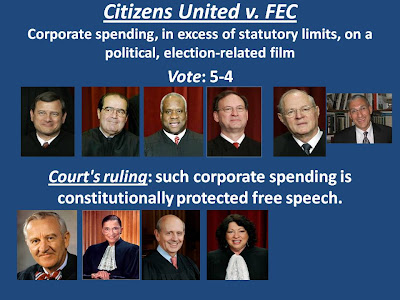

First we'll look pictorially at my hypothetical votes alongside the Justices' real ones in each of the cases. Later, we'll look graphically at my hypothetical record alongside the real ones for the Justices--restraint versus activism, and politically conservative versus politically liberal.

So here, again pictorially, with minimal explanatory text, is how I would have voted in the "Top Ten" highlight cases of last term. There is no special order. Just the order in which they happened to have been discussed in the preceding posts in this series.

As I discussed in a previous post, I would have sided with the conservative Justices in Citizens United. Best to be extremely resistant--and I do mean extremely--to any government attempt to restrict expressive political activities. The 1st Amendment is stated in absolute terms, and I'd apply it as close to that as possible.

In Humanitarian Law Project, as in the campaign finance case, I'd be extremely resistant to government attempts to stifle expressive political activity. Criminalizing entirely peaceful speech, by a peaceful humanitarian group, about peaceful advocacy, seems a very unjustified stretch--even in the name of the war on terror. So, I'm with the 3 liberal dissenters in this case.

No right, including free exercise of religion is absolute. In Christian Legal Society, the state university's ban on discrimination against gays and lesbians--like prohibitions on other forms of invidious discrimination--outweighs a student religious group's entitlement to university recognition and funding. Student groups, religious or otherwise, can believe whatever they want and exclude whomever they want, but not with government support. I'm with the libs + Kennedy here.

In Hollingsworth, there was simply no good reason to deny interested citizens the ability to watch the same-sex marriage trial on closed circuit TV (in limited venues--several federal courthouses around the country). The Supreme Court majority's argument--in overruling the federal judge and the federal appeals court which had agreed to televising the trial--was quite lame and almost assuredly pretextual: some witnesses testifying against (or for) same-sex marriage might encounter hostility outside the courtroom. Well, that's an argument for banning public trials--with or without closed circuit--whenever the issue is contentious.

In Buono: a cross, honoring those who were killed in military combat, displayed on a patch of land in an expansive national preserve? One may support a very strict Jeffersonian separation of church and state--as I do--and yet still conclude that this is too de minimis to rise to the level of government's embrace of a religion in violation of the Constitution. Seems de minimis to me.

In Padilla, the attorney's mistakenly assuring his client that he would not be deported if he pleaded guilty was pure incompetence. If the attorney didn't know--which he didn't--he shouldn't have spoken. Beyond that, the attorney should have known about something so critical to his client by looking up the law and advising his client correctly. So, I'm with the libs on this one--i.e., ineffective assistance of counsel. And I don't think Roberts and Alito's splitting the difference here (see second Padilla pictorial immediately below) is adequate.

No permanent life sentence for a non-homicidal crime committed by the defendant while a juvenile. Not ever? Regardless of the crime or aggravating circumstances? What about a second or third brutally violent rape of an infant by the defendant when he was a day or two short of 18 years of age? Well, that's my point. I can't say never to such a sentence. I'm with Roberts on this one. (See the pictorial immediately below.) The sentence may be too harsh for the burglary in Graham. But I can't say that the sentence would never be justified.

In Berghuis, nothing involuntary, nothing compelled, nothing harsh or brutish or coercive, no indication of anything in the confession that was misspoken or unintended or otherwise unreliable. The defendant was given Miranda warnings and he later chose to speak of his own accord. I'm with the conservatives on this one.

Why throw out an entire statute? To make a point that Congress ought to write laws more clearly? Well, of course it should. But, instead of spanking Congress to teach it a lesson, why not do what judges should do and save what is clear--and clearly constitutional--about the law. In Skilling, the prohibition of bribery and kickbacks is clear and clearly constitutional. I'm with the majority.

The right of individuals to bear arms was considered fundamental to freedom by the Founders and the Framers--a protection against tyranny and a matter of self-defense. That's historically clear, regardless of what the wording of the 2d Amendment itself was intended to guarantee. Of course, this right--like all others--is not absolute. But it is a continuing part of our national heritage and tradition and belief. It should be applicable against the states like all other fundamental rights. I'm no fan of guns, but the conservatives got it right in McDonald.

Well, that's how I see the issues in those cases, and that's how I'd have voted. Undoubtedly, some of that colored how I discussed the "Top Ten" highlight cases in the previous posts in this series. In the next post, a few of those fan-pleasing graphs to put all the foregoing together.